ABSTRACT

The adoption of green technology is a vital step toward combating climate change and promoting sustainable development. However, the economic impacts of this shift, especially how income inequality influences the speed of adoption, remain a major concern, particularly in developing countries. This paper explores the complex relationship between adopting solar technology and income inequality, focusing on how different socioeconomic groups in Nigeria are affected by this technological change.

Keywords: Green Technology, Income inequality, Climate Change, Sustainable Development

I. INTRODUCTION

In this paper we examine how the adoption of green technology is influenced by income disparity in developing countries given enabling factors such as high unemployment rates, poor financial access and inclusion, reduced job creation and difficulty in doing business. Although, green technological innovations are aimed at lowering environmental impact through provision of renewable energy, production of energy-efficient appliances and electric vehicles, and development of sustainable farming practices, the ripple economic effects and wide spread income inequality especially in developing countries like Nigeria makes the full-scale adoption difficult.

While its environmental benefits are well-supported, this paper will analyses its economic effects and the influence of income inequality in the implementation of solar technology amongst households in Nigeria. Our hypothesis is that solar technology adoption is slower amongst the poor socioeconomic groups in developing countries due to widespread income disparity.

This hypothesis test is important because the country highlights a context of unreliable power supply and a high reliance in unsafe environmentally harmful options — like diesel and petrol generators. I employed descriptive analysis on latest Nigerian socioeconomic data between different income classes and commercial data on the initial cost outlay of solar technology to define the reason for the slow adoption amongst the lower class as the high initial cost outlay, hence the continued reliance in unsafe and harmful options.

It is evident that despite the environmental issues associated with generators, most Nigerians cannot afford a clean alternative due to the steep upfront costs of the alternative options. Therefore, the economic implications of the transition to green technology in the light of the effect of income inequality on how quickly people adopt it —remain a major concern.

It is worthy to note that despite the impact of income inequality on adopting green technology, global action to support its implementation is clear. This continued support is vital for combating climate change and achieving sustainable development. In line with the global actions and support for this drive, we will take a further deep dive into blended finance options which is focused on increasing financial access to support the application of green technology in developing countries like Nigeria.

To promote widespread adoption, the main challenge is financial which requires innovative funding solutions to make green technology affordable for the masses. Blended finance models and other forms of capital which leverage funds to de-risk individual burdens, are therefore essential for closing the affordability gap and speeding up the deployment of green solutions like solar technology across Nigeria’s diverse income groups.

II. Literature Review

A.1 Income Inequality, Solar Adoption, and the Blended Finance Solution

Nigeria, like many developing nations, faces significant challenges with economic inequality and environmental decline. With a large rural population and high poverty levels, the adoption of renewable energy, particularly solar power, is heavily limited by income disparity, lack of access to technology, and inadequate infrastructure.

Most low-income households in Nigeria depend on unreliable grid power or have no access at all. Solar energy, as a clean and sustainable alternative, could provide a solution. However, high installation costs and upfront investments remain significant hurdles, especially for the poor. Limited access to technology and financing, along with regional economic disparities, widen the gap between the rich and the poor in adopting climate-friendly solutions.

Although government actions and private sector efforts have been made to address these challenges, the unequal distribution of income and resources still impedes the adoption process. Addressing income inequality is essential for a fairer transition to sustainable green technologies, especially in underserved areas. The benefits of adopting green technology cannot be overstated.

This includes:

Enhanced Access to Energy: Installing solar technology enables low-income households to access reliable and sustainable energy, reducing their reliance on environmentally harmful sources like generators powered by diesel or petrol.

Improved Quality of Life: Reliable electricity provides households with better opportunities for education, healthcare, and economic growth.

Long-term sustainability: Solar systems stay operational for a long time, promoting the adoption of green technology and offsetting the high upfront costs.

A.II The affordability gap in Nigeria: Case Study

AII-a. Energy Requirement for a Household in Nigeria Versus Living Income

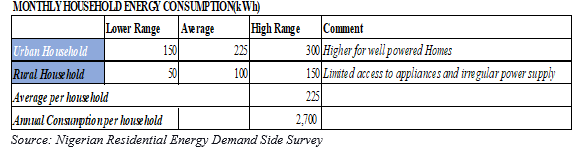

Table 1: Average Household Energy Need

In Nigeria, household electricity use varies widely depending on location, grid access, and lifestyle. It is estimated at 162.5 kWh per month or 1,950 kWh annually.

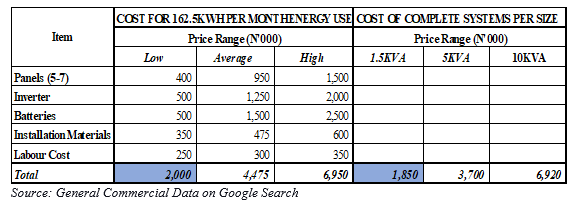

Table II: Total Average Solar Cost

Average Solar Cost is estimated at N1.85million Using 165kWh per month consumption and N2million based on a 1.5KVA sized solar system.

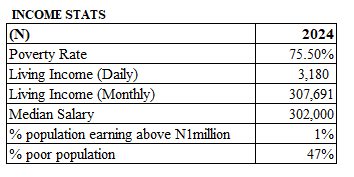

Table III: Low-Income Living Reality

Source: Anker Research Institute/Global Living Wage Coalition, National Bureau of Statistics, Central Bank of Nigeria, World Bank’s Nigeria Poverty and equity brief.

Poverty is more widespread in Nigeria’s rural areas, where the poverty rate has risen to as high as 75.5% (living on less than $2.15 per day as of 2024).

To meet basic needs in rural Nigeria, studies estimated the living income to be ₦307,691 per month (around $208) in mid-2024. This is similar to the estimated median salary of N302,000. This median income of the population is far below the amount needed to afford the smallest complete solar system. Data collected in April 2025 showed that less than 1% of Nigerians earned more than NGN 1 million per month.

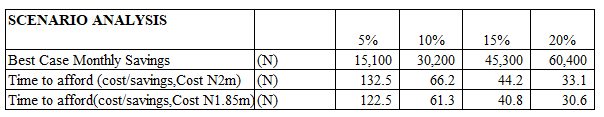

Table IV: Affordability Analysis

Best-case scenario (with savings): Assuming a highly unrealistic 20% savings rate from the monthly living income, the time to afford would be roughly 2.8 years for a solar system costing N2 million and 2.6 years for a solar system costing N1.85 million.

Most likely scenario (without savings): If a household has no disposable income after covering basic needs, it cannot save any money and will never be able to afford it without financing.

Other factors to consider:

- Actual costs: The ₦2 million figure reflects the average price for a smaller residential system; however, the total cost can be substantially higher once installation and maintenance are included.

- Informal economy: Many rural Nigerians work in the informal economy, where income is often irregular and unpredictable. The irregular and unpredictable wages make consistent saving more difficult.

- Low Income Population: A ₦2 million purchase would amount to two or more months of income for even these high earners in the 1% category earning above a million per month, making it not “convenient” to afford.

* Fewer than 1% of Nigerian residents earn enough to afford a N2 million solar power system upfront, based on income distribution data from 2024 and 2025.

A.III Blended Finance: Bridging the Gap

To address this significant affordability gap and facilitate a more equitable transition to sustainable green technologies, the Nigerian market may explore solutions through blended finance.

Blended finance involves using catalytic capital, usually from development finance institutions (DFIs) or philanthropic funds (the “public” money), to reduce risk and attract much larger amounts of commercial capital (the “private” money) into projects that are vital for sustainable development but are currently considered too risky for solely commercial investment.

In the solar adoption context, blended finance can:

- Subsidize Initial Costs: By using public grants or concessional loans to lower the high upfront cost of solar equipment, repayment plan becomes manageable based on the affordability gap and can be arranged depending on each individuals cash flow.

- Guarantee Commercial Loans: Provision of guarantees to local financial institutions, encourages them to lend to low-income customers who lack traditional collateral making the green technology adoption more widespread with financial access.

- De-Risk “Energy as a Service” (EaaS): By supporting companies offering Pay-As-You-Go (PAYGO) solar models, blended finance transforms a high capital expense into a manageable operating expense.

A.IV Case Studies in Blended Finance

Companies operating in Nigeria and the broader African market demonstrate how this model works, often integrating finance seamlessly into the product delivery. Below are two major front liners in this space:

- M-KOPA (East Africa/Nigeria): A leader in the PAYGO model, M-KOPA leverages mobile money and embedded finance to enable low-income customers to buy solar home systems, smartphones, and other products through small daily or weekly payments. The solar asset often serves as collateral, and payments are handled digitally—demonstrating how finance can be deeply integrated into the service.

- Moniepoint (Nigeria): While mainly a large mobile money and business banking platform, they built a crucial infrastructure supporting blended finance by providing the essential digital financial infrastructure to enable PAYGO payments, collect micro-installments, and monitor repayments for green financing models. The success of this structure is attributable to their extensive network of agent banks and deep reach into underserved and rural areas. Moniepoint’s PAYGO solar model operates effectively at scale, this underscores the importance of a strong, integrated payment infrastructure in achieving a sustainable blended finance solution to bridge the affordability gap in green technology adoption.

III. Conclusion

The gap between economic inequality and the urgent need for green technology in Nigeria remains large. As shown by the cost analysis, solar technology is still out of reach for most people using traditional methods. Widespread adoption can only happen through affordable green financing, especially models supported by blended finance.

By strategically leveraging public and philanthropic funds to de-risk investments, blended finance enables private sector-led, innovative models like PAYGO (championed by firms like M-KOPA) and depends on strong local payment infrastructure (such as that provided by Moniepoint).

Applying this financial approach will not only help Nigeria reduce reliance on generators and mitigate climate change impacts but also boost economic productivity, generate jobs, and promote a fairer, more sustainable energy transition.

Reference

Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P., & Zilibotti, F. (2012). Distance to frontier, selection, and economic growth. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(1), 270-305.

Anker Living Income Reference Value / Global Living Wage Coalition update for Rural Nigeria (2024 update). https://www.ankerresearchinstitute.org/nigeria-home

Brock, W. A., & Taylor, M. S. (2005). Economic growth and the environment: A review of theory and evidence. In P. Aghion & S. Durlauf (Eds.), Handbook of economic growth (Vol. 1, pp. 1749-1821). Elsevier.

Diego A. Barrado-Timon, (2016) Reflections on public space as a common value Puerta del sol (Madrid) between los indignados and Vodafone, or who is occupying what – Working Paper Series -contested cities. http://contested-cities.net/working-papers/2016/reflections-on-public-space-as-a-common-value-puerta-del-sol-madrid-between-los-indignados-and-vodavone-or-who-is-occupying-what/

Grossman, G. M., & Krueger, A. B. (1995). Economic growth and the environment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(2), 353-377

IBM. ‘’ Green Technology’’ . https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/green-technology

Jaffe, A. B., Newell, R. G., & Stavins, R. N. (2003). Environmental policy and technological change. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(4), 1303-1360.

Lal, A. (2009). An Empirical Time Series Model of Economic Growth and Environment. https://core.ac.uk/download/211617890.pdf

Marin, B., & Vona, F. (2019). The environmental Kuznets curve: A critical review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(3), 738-773.

Markus Schneider Solutions. Harness the Power of AI for Next-Level Leadership Development – https://markusschneidersolutions.com/your-digital-vision-partnership-which-creates-a-secure-competitive-advantage/

Michael, C., & Izedomi, I. (2025). Insurance Sector Development and Economic Growth: A Case Study of Nigeria From 2000-2023. The Journal of Developing Areas, 59(2), 171-185.

Panagoret, A., & Panagoret, A. (2022). Financial Performance under the Impact of the Decision to Implement an Organizational Change. Sustainability, 14(21), 13932.

Retech, Green Technology: Building a Sustainable Future – https://www.retech2010.com/green-technology-building-a-sustainable-future/

Rinki Sisodia (2024). Top 10 Advantages of Electric Vehicles. https://www.evmechanica.com/top-10-advantages-of-electric-vehicles/

Rothwell, C. J., Freedman, M. A., & Weed, J. A. (2013). The National Vital Statistics System. Springer E Books. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4471-4237-9_17

Stern, D. I. (2004). The rise and fall of natural resources. Economic Inquiry, 42(2), 1-34

Wikipedia. ‘’ M-Kopa’’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M-Kopa#

World Bank. “Blended Finance”. https://ppp.worldbank.org/blended-finance.

Leave a comment